Zuma, Mugabe and Desalegn may be gone but democracy in Africa is far from mature

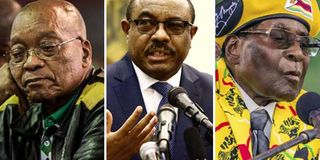

South Africa’s Jacob Zuma (left) and Ethiopia’s Hailemariam Desalegn (centre) were booted out of office within 60 days of Mugabe’s (right) ouster and it would have sounded like a mad man’s wager. FILE PHOTOS

What you need to know:

Jacob Zuma door was always unpopular with the powerful elite in the ANC and his appetites invariably led him astray.

In 2000, the Economist judged Africa too soon and saw hopelessness where significant changes had already happened.

In Zimbabwe and Ethiopia, the ruling elites differed on how best to secure their parties’ long-term interests.

Who would have guessed this time last year that by year-end Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe — the world’s oldest head of state — would be out of office? Yet he was forced out at 93 years and after 37 years in power.

Add to that the odds of South Africa’s Jacob Zuma and Ethiopia’s Hailemariam Desalegn being booted out of office within 60 days of Mugabe’s ouster and it would have sounded like a mad man’s wager.

In January 2017, Mugabe was unassailable. He had a long record of out-foxing his opponents.

Jacob Zuma next door was always unpopular with the powerful elite in the ANC and his appetites invariably led him astray.

Yet his grip on the party’s grassroots gave the impression that he could survive any crisis, at least until the 2019 election.

ETHIOPIA

In Ethiopia, Prime Minister Desalegn of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) never looked as secure as his more autocratic predecessor, Meles Zenawi, but the party had neutered its opponents so comprehensively, it would have been unthinkable that Desalegn would be forced out by a popular uprising.

Expect breathless and hyperbolic claims from the talking heads about what these civilian coups mean.

Extravagant claims not justified by facts are already being made.

JUDGED TOO SOON

In 2000, the Economist judged Africa too soon and saw hopelessness where significant changes had already happened but not filtered through to economic statistics.

McKinsey and Co were surprised by Africa’s resilience in the face of the 2008 global financial meltdown and immediately tooted a renascent continent that the Economist sanctified with its ‘Africa Rising’ cover.

In 2011, the Arab Spring was trumpeted as a harbinger of popular revolutions eastwards to the gulf and southwards to sub-Saharan Africa. The problem, as always, is lack of a granular understanding of the forces behind events in Africa. The events in South Africa, Zimbabwe and Ethiopia are hardly tipping points towards democracy.

ELITES DIFFER

In Zimbabwe and Ethiopia, the ruling elites differed on how best to secure their parties’ long-term interests.

Mugabe wanted a bigger say in the future of Zimbabwe against the interests of those who had kept him in power for so long.

The new South African commercial class feared that a few more months of Zuma’s leadership would hurt their party’s long-term interests, perhaps even erode their base so much that they might need a coalition partner in 2019.

In Ethiopia, the EPRDF has been hit by a perfect storm that its generally smug leadership never saw coming. Desalegn’s exit suggests party bosses have been freaked out by the depth and persistence of the Oromiya rebellion even as they have grown frustrated by Desalegn’s ineffectual leadership.

Only now, since the Oromiya crisis began three years ago, has the EPRDF seen the danger those protests pose both on its hold on power and to the legacy of Meles Zenawi.

Let us drill down into each of these three cases.

In Zimbabwe, the Mugabe State is intact even after his exit. Mugabe is out of power from the foibles of age mixed with romantic folly and oligarchic blindness.

He tried to smooth his wife’s path to the presidency against the interests of the power men — and they are all men — who had kept him in power these last few years. He misunderstood the tacit bargain on which their support rested: They would let him live out his days in office if he let them settle on his succession.

Emmerson Mnangagwa, the man who has replaced Mugabe at the helm, was the Zanu-PF enforcer, a man with strong links to the security machinery.

The mantra “anyone but Mugabe” ducks a crucial question: How does Mnangagwa represent change? Mnangagwa and the army — backed by veterans — have cleverly re-framed the ouster of Mugabe as remedial, an action targeted at the “criminals” around Mugabe “who are committing crimes” that cause “social and economic suffering in the country”. The truth is that, as in Egypt, the men in uniform are running the show. As before.

The Ethiopian crisis, the worst in the country since the Tigrayan-dominated EPRDF came to power in 1991, began in Oromiya in 2015.

In 2016, it caught on in parts of Amhara. That’s a worry: The two regions hold 62 per cent of Ethiopia’s 96 million people, but their grievances are different. Amhara wants Tigrayans — who form six per cent of the population — to give back some land they are holding. Oromiya wants an end to northern dominance.

NEWS BLACKOUT

Though hundreds have been killed, the crisis did not look as serious to outsiders, thanks to a news blackout, a government-controlled media and widespread repression. Even now, the EPRDF is still rather inept. It has imposed emergency rule.

It is trying, again, what it did in 2016 — pre-selecting which Oromo leaders to talk to, actions that further alienate the Oromos and the Amharas and feed their already fractured trust. In the early days of the conflict, Ethiopia called the protesters lackeys of foreigners — read Eritreans — who Ethiopia fought a border war with, and Egyptians — who are unhappy with Ethiopia for building the Renaissance Dam, affecting the flow of the Nile.

The conflict arises from Ethiopia’s dangerously bifurcated state. Political power has always been with the north — in the Tigrayan and Amharic heartlands of old Abysinnia — whilst economic power lies in the central and the southern regions, especially Oromiya and the Southern Nations and Nationalities People’s Regional State (SNNPRS).

REPRESSION

Meles’s authoritarian bargain, which entailed repression in return for prosperity, was always fragile because economic progress could only be achieved by the efforts of regions excluded from political power.

Desalegn is from the south but he was a marginal figure at the heart of Ethiopian politics and Zenawi’s tokenist gesture to a region he never quite understood.

The Oromos resent the Amharic and Tigrayan dominance of Ethiopian politics. The two have often mythologised their privileges by their supposed links with King Solomon and his consort, the Queen of Sheba. Their rival claims pan out as follows.

The Tigrayans, probably the first people to use the name Ethiopia, are heirs of the Aksumite Kingdom (100AD to 940 AD), a sophisticated trading society that minted coins widely used in international trade and built the impressive stelae for which Ethiopia is famous. Axum, their capital, is supposedly the home of the lost Ark of the Covenant. It is also said to have been the home of the Queen of Sheba.

The Amharas also claim a link to Solomon. They say the founder of the Amharic dynasty, Menelik 1, who was king around 950BC, was King Solomon’s son with the Queen of Sheba.

There is little evidence for this except claims made in the Kebra Negast, an Ethiopian creation myth described by one scholar as “a gigantic conflation of legendary cycles”.

SOLOMON LINK

The Amharic link to Solomon goes back to the 13th century when Yekuno Amlak I came to power claiming descent from Dil Na’od, the last King of Axum with a link to Solomon. It is he that re-established the dynasty that ruled Ethiopia until 1974, when it was overthrown by a Marxist Leninist junta, the Derg, headed by Mengistu Haile Mariam.

Mengistu, the butcher of Addis Ababa, resented the Tigrayan and Amharic elite, whom he thought of as racist slavers.

However, his excesses united many traditional foes into a common cause against the Derg. At one point, the Tigrayans from Ethiopia and Eritrea, then a region of Ethiopia, formed a fragile alliance with the Oromo Liberation Front, an Oromiya rebel group founded in the early 1970s to fight Amhara dominance.

The Oromos wanted to secede from Ethiopia but were persuaded to stay partly because the 1995 Constitution recognised a right to secede.

Then, Meles managed Oromiya by divide- and-conquer tactics and by crushing the Oromo Liberation Army. He centralised power, controlled and manipulated elections, harassed and jailed the opposition, but fobbed off Western critics by his commitment to honest government and his impressive development record.

LOST COHERENCE

When Meles died in August 2012, the centre gradually lost coherence as competing elites jostled for influence. Desalegn is a Wolatya, a small ethnic group from the SNNPRS.

He neither had the authority of Zenawi nor the necessary links to the structures of Tigrayan power. Religion is an unstated factor.

Desalegn is a Pentecostal, a group that forms fewer than 10 per cent of the population even when combined with evangelicals. A majority of Ethiopians, 44 per cent, are Ethiopian Orthodox, a faith dominant among the Tigrayans and Amharas. The Protestants are dominant in the SNNPRS (more than 50 per cent of the population) and Oromiya where they form 20 per cent.

Kicking out Desalegn won’t address the roots of the crisis. In the short run, the EPDRF will continue flailing unconvincingly against foreign enemies.

The reforms the government is promising are likely to be a re-shuffling of the elite at the centre of power in Addis Ababa. That, unfortunately, won’t set Ethiopia on the path to democracy any time soon.

In South Africa, Zuma lost because he waged war on the constitution.

His attempts to compromise and weaken institutions, including Parliament and the Judiciary, all to stave off his personal problems risked the ANC’s hold on South African politics.

SUPPORT DWINDLING

With elections due in 2019, the ANC must have noted that since 2004, support for the party has been dwindling. That year, the party won almost 70 per cent of the vote.

This had fallen to 62 per cent by 2014. In the 2016 municipal elections, the ANC got a real scare from the Democratic Alliance.

The Alliance won in Pretoria and only narrowly lost in Johannesburg, where with only 44 per cent of the vote, the ANC barely scraped through.

This was the first time that the ANC had lost in the capital. The outlook for 2019 was bleak. Thanks to South Africa’s parliamentary presidency, the president is elected by Parliament and so by the party with the largest number of MPs.

As a result, the ANC was able to oust Zuma before his escalating difficulties could irreparably damage its chances for 2019.

In all the three cases then, the power elite got rid of the leader to preserve itself but with this difference: In South Africa, the ANC had to credibly recommit to democracy and honest government to avoid an electoral catastrophe in 2019. In Ethiopia and Zimbabwe, the incumbents had become a threat to elite control of the State.

The changes in South Africa are likely to help reclaim its democracy. But those in Zimbabwe and Ethiopia will not.