Congolese people carry their belongings as they flee from their villages around Sake in Masisi territory, following clashes between M23 rebels and the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo on February 7, 2024.

The conflict in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has often brought out stories of atrocities: People killed, displaced, raped or maimed. It is a cycle of the last 30 years.

But the main victims, and weapons, in this have often been refugees. The victims though are sometimes also the pawns in this war where parties change often just like interests.

After a tense meeting in Addis Ababa with the mediator João Lourenço, President of Angola, Rwandan President Paul Kagame and his Congolese counterpart Félix Tshisekedi are expected to meet again before the end of February, according to the Angolan Presidency.

But Tina Salama, spokeswoman for the Congolese president, while confirming readiness for another dialogue session, indicated that “President Tshisekedi is not going to talk to the M23. He will do so with Rwanda, but not at any price.” She was referring to the rebel group Kinshasa says is backed by Rwanda, a claim Kigali denies.

Among the issues the two countries should hold talks on is the question of refugees on both sides. The history of Rwanda and DRC is such that past and present conflicts on either side have left each hosting refugees from the other. Those refugees have not always been seen as victims though.

Take the case of the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), the remnants of the perpetrators of the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi, now operating as a rebel group inside the DRC. They are mainly of Hutu ethnicity who fled Rwanda when the Paul Kagame-led Rwanda Patriotic Front army defeated them. They entered DRC, then known as Zaire, as refugees.

Those refugees included civilian populations, remnants of the fleeing administration, the army, the police and the central bank officials.

“Everything was brought to us,” argued former Congolese Prime Minister, Léon Kengo, in his memoirs, Le Passion d’Etat, about the episode in 1994. He had been appointed two months after the arrival of these refugees, in April 1994, whose violence arose from the plane crash in which then Rwandan President Juvénal Habyarimana and his Burundian counterpart Cyprien Ntaryamira were killed.

At the time of these tragic events, the Zairian government, then led by Prime Minister Faustin Birindwa, "tried, as best it could, to manage the problem, but the stakes were too high,” Kengo wrote.

When Kengo wanted to repatriate these refugees to Rwanda, under a United Nations Security Council resolution for voluntary repatriation, neither Kinshasa, nor Kigali, nor even the UN could force them to return to their country.

Even the proposal to separate the combatants from the civilians among the refugees and relocate them to other provinces of the DRC failed, former UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutros Ghali having judged the cost of this operation too exorbitant.

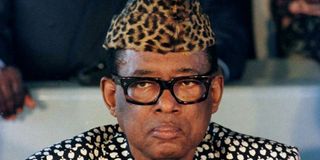

Former President of Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) Mobutu Sese Seko.

In reality, for President Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire, the refugee issue was becoming a stake for his rehabilitation in the eyes of the international community. The former president, who had previously been ostracised by Western countries and international organisations, was taking advantage of the reception of Rwandan refugees, at the behest of the West, to restore his image and relaunch himself internationally.

Even then, “Rwanda opposed the return of the refugees, claiming that they were armed former genocidaires who were preparing to attack the country”.

Over the years, as relations between Rwanda and the DRC deteriorated, Kigali began to declare that Kinshasa was working in concert with the FDLR rebels.

Rwanda claims that this issue “represents a serious threat to Rwanda’s national security”. “It will not be accepted for the problem to be externalised into Rwanda, by force, once again,” the Rwandan Foreign Ministry said in a statement last week.

These allegations were rejected by the Congolese authorities, who in turn described the war in the Kivus, eastern border provinces, as “a war imported into the DRC by Rwanda”.

Back in 1994, Léon Kengo had already warned Mobutu, telling the ‘Marshal of Zaire’ that “all this management procrastination will cost (us) dearly in the future”.

It has to be said that the prime minister had wanted an enforced repatriation, while Mobutu had declared that these refugees could only return to Rwanda voluntarily.

“Meanwhile, Rwanda kept threatening to attack the refugee camps in our country. Sometimes it was in favour of this return, sometimes it feared it,” writes Kengo.

Kabila’s arrival

What followed was the arrival on the scene in 1996 of Laurent Désiré Kabila’s Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire (AFDL) rebellion, supported mainly by Rwanda. This rebellion massacred refugees gathered in camps.

The wars that have followed since then have forced many Congolese to seek refuge in neighbouring countries, including Rwanda. According to the United Nations, one million Congolese have fled to neighbouring countries.

Two displaced Congolese women stand on a hill overlooking new homes built in a camp for the internally displaced in Katoyi in Masisi territory in the Democratic Republic of the Congo's North Kivu on June 4, 2012. Some 1,500 families fled to Katoyi following fight between FDLR and Mai Mai rebels.

The UN refugee agency, UNHCR, estimates that around 81,000 Congolese have found refuge in Rwanda. The UNHCR also estimates that 209,000 Rwandans are refugees in the DRC.

In January 2023, at the height of the M23 war in the DRC, a controversy arose between Kigali and Kinshasa when President Kagame declared that Rwanda could no longer accept refugees from the DRC.

Last May, the DRC and Rwanda undertook to enter into “constructive dialogue in order to create favourable conditions” for the sustainable return of Congolese and Rwandan refugees to their respective countries.

A meeting was scheduled to take place in Nairobi in June 2023 to define, on the one hand, the practical modalities for reactivating all the commitments and structures contained in the 2010 Tripartite Agreements and developing a comprehensive roadmap. On the other hand, they were to relaunch the process of facilitating the voluntary repatriation of Congolese refugees in Rwanda and Rwandan refugees in the DRC, in accordance with the guiding principles and modalities already subscribed to in the text of the 2010 Tripartite Agreements.

The May 2023 meeting was attended by Congolese delegations led by Christophe Lutundula, the Deputy Prime Minister in charge of Foreign Affairs; Marie Kayisire Solange, the Minister for Emergency Management of the Republic of Rwanda, and the UNHCR High Commissioner Filippo Grandi. Since then, however, no further progress has been reported on this issue.